11 November 1940, first moment of resistance in Paris

On 11 November 1940, a few months after the start of the occupation of parts of France by Nazi Germany, hundreds of Parisian high school students and university students decided to demonstrate on the Champs-Élysées towards one of the capital’s most emblematic monumenmts, the Arc de Triomphe (Arch of Triumph). The date chosen, that of the commemoration of 11 November 1918, was symbolic: the victory over Germany during Wolrd War One. This deonstration appears to be one of the first coordinated public acts of resistance on French territory following the appeal of 18 June 1940 from General De Gaulle from London.

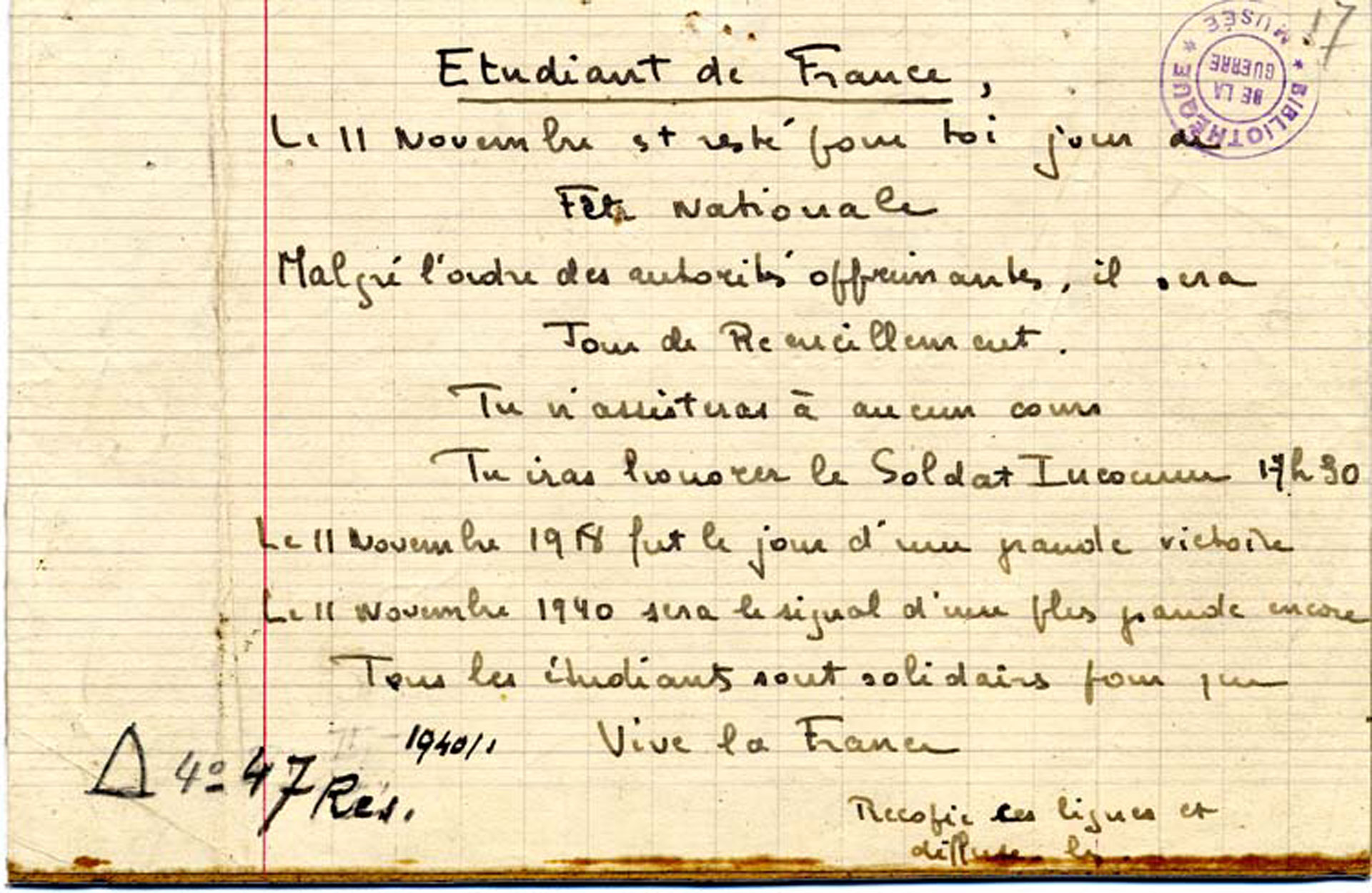

In a city transformed by the omnipresence of Nazi uniforms, road signs in the German language and swastika flags, Parisian youth mobilized rather quickly and courageously in the face of oppression. Life having returned to normal after the panic of the first weeks, the start of the school and university year had taken place almost normally to the extent that the majority of civil servants and teachers are adapting to the situation. This was without taking into account the rebellious attitude of certain students driven by a spirit of resistance. From September, particularly in the Latin Quarter, students throw eggs or tomatoes, draw the “V” for victory in white paint on walls, shout “Vive De Gaulle” in subway corridors and put anti-Nazi leaflets in libraries. The decision of the Vichy government to no longer commemorate 11 November and to no longer make it a public holiday, combined with the arrest of Paul Langevin, professor at the Collège de France and a true scientific authority, turned the ambient discontent into a more structured movement, motivated by a rejection of the German occupation, and which reached its climax on the 11th.

That day, at dawn, groups of students come to lay flowers at the tomb of the unknown soldier placed under the Arc de Triomphe, symbol of heroism against Germany. At the end of the afternoon, when there were nearly 3000 gathered, singing La Marseillaise (national anthem of France) or “Vive De Gaulle” (Long live De Gaulle), the German army, helped by the French police, decided to intervene with rifle butts and weapons fire to disperse the demonstrators whose average age is barely 18 years old. Around fifteen injuries were reported as well as around 200 arrests followed by imprisonment. The next day, all universities in Paris were closed for a few weeks by the German military command.

Remarkable because it took place only some months after the occupation of France, this first public act of resistance had no real political roots even if some high school students had proven communist sympathies. While a silent majority resigned itself to a degrading occupation, these young people showed the way: to push back barbarism we will have to get involved.

Yvan Gastaut