Unlikely calling: the Yugoslav Partisan priests

Becoming a priest for an army led by the communists may have certainly seemed like an unlikely calling. Without a doubt, most of the clergy of all three major religions in occupied Yugoslavia, Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Islam, keeping in line with tradition and conservative outlook, either stayed “neutral” or sided with the nationalist movements and regimes. Significant parts of the Croatian Catholic hierarchy supported the Ustasha regime and some of its policies, while taking advantage and converting many of the persecuted Orthodox. Some took off their robes and put on uniforms, like Miroslav Filipović, who was expelled from the Franciscans in 1942 and executed as a war criminal in 1946.

The position of the Serbian Orthodox Church was more complicated. Due to its anti–German stance, it did not truly support the quisling regime in Belgrade. Many of its priests sided with the Chetniks, some as combatants. In the Independent State of Croatia, where Orthodox clergy was heavily persecuted by the regime, priests like Momčilo Đujić in Dalmatia and Savo Božić in northern Bosnia became Chetnik commanders. Because of such alliegencies, around 150 Orthodox clergymen and nuns were targeted by the Partisans during the war, in contrast to 370 killed by other forces.

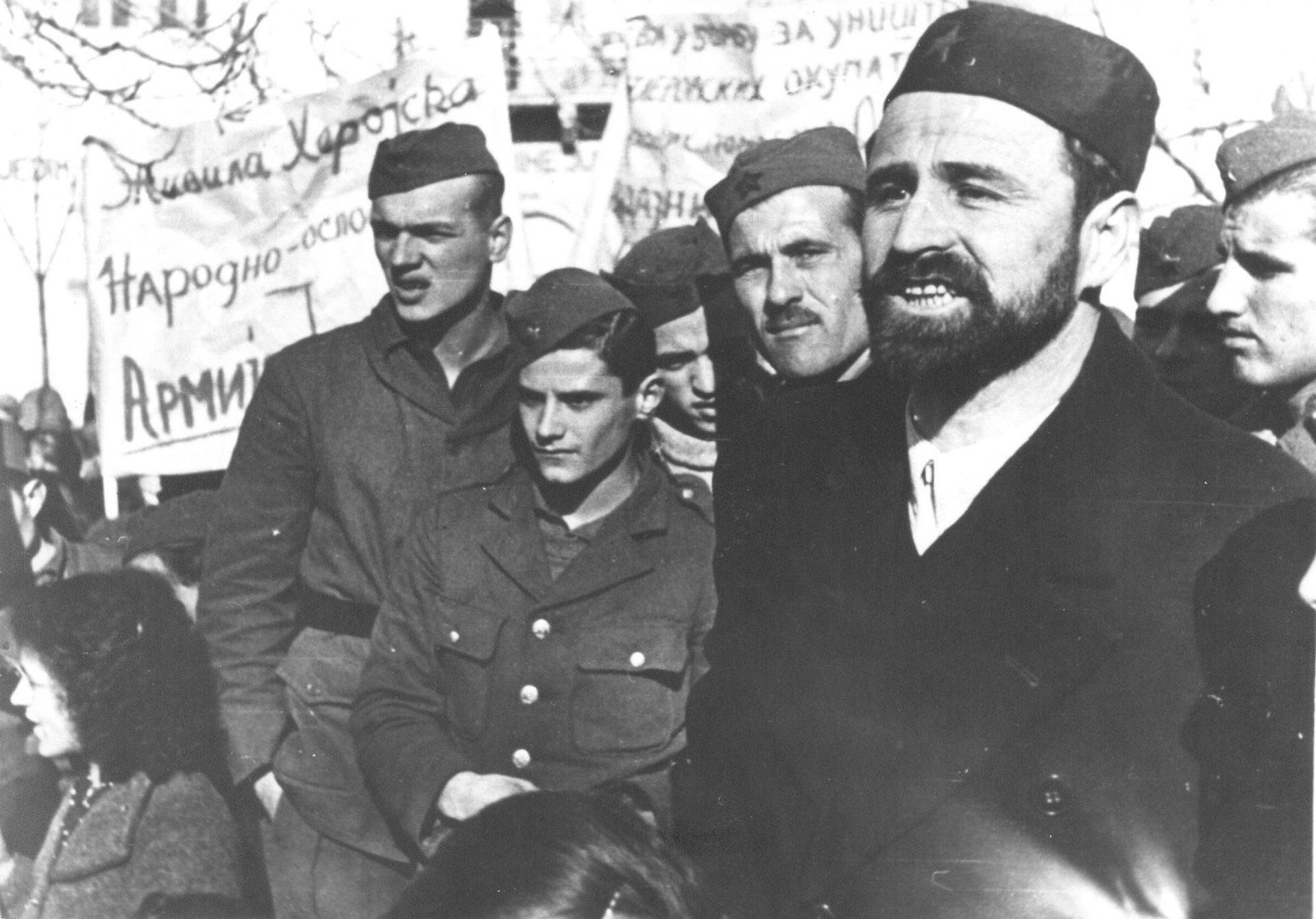

And yet, some priests fought on the other side as well. Almost 80 Croatian Catholic priests joined the Partisans and over half lost their lives. Svetozar Rittig, parson of the St. Mark Church of Zagreb, supported the movement from the start. As a speaker before the Second Session of AVNOJ he exclaimed that he had never before attended an assembly with such healthy thoughts, which are to him as “bright as Easter”. The Partisan command established the position of “religious clerks”. Orthodox priest Jevstatije Karametijević and imam Sead Musić served together in the same brigade. The best known Partisan Orthodox priest was Vlada Zečević, who organized his own Chetnik detachment and then switched sides. Like Rittig, he would remain a prominent name in postwar politics. In November 1942 Zečević organized the first assembly of pro–Partisan Orthodox priests. Another priest was Novak Mastilović from Herzegovina, who managed to escape the 1941 June pogroms organised by the Ustasha and then joined the uprising. At the first session of ZAVNOBiH in 1943, which he attended as a delegate, Mastilović declared that the greatest success of the movement was that it prevented inter–ethnic revenge. He appealed to other clergymen to help further fraternization among the communities. To him this was a necessary prerequisite for final liberation.

Vladan Vukliš & Nataša Mataušić